And we’re back!

All defrosted and ready to forge on as if there wasn’t an icy chunk of months missing from that archive menu! All I can say is that, as always, life intervened! But these comics are just as important to me as ever, and, after considering a plan to keep on Capping in podcast form, I’ve decided that only print can do justice to these babies. There’s something about Mark Gruenwald’s writing that brings out the literary theorist in me… which isn’t necessarily a good thing, of course… but, for better or for worse, when I sit down to read the man’s work, I stay seated, and my fingers reach for the keyboard, rather than the mic! So here we are again–just in time to run parallel with a Captain America film that won’t have any of the thoughtful qualities that Gruenwald’s iteration of the character displayed in such abundance… All the more reason to take a closer look at it, wouldn’t you say?

Well, I hope you agree, ’cause here comes

(See? How do you discuss that title in a podcast?)

(See? How do you discuss that title in a podcast?)

Writer: Mark Gruenwald

Pencils: Paul Neary

Inks: Dennis Janke

Colors: Ken Feduniewicz

Letters: Diana Albers

Editor: Mike Carlin

Let’s pick up where we left off (before The Beyonder bumbled into the storyline, by company decree)

Gruenwald, always the most architectural of comics constructionists, had us all primed for a three-way standoff between the conveniently-named figures featured in this issue’s title. And now that we no longer have that idiotic crossover to bear, he delivers an extraordinary ego triptych which effortlessly sets the stage for an entirely new (and yet, to me anyway, almost inevitable) take on the legendary Star Spangled Avenger.

This issue further develops the portrait of mid-Reaganian America begun in #307. As I noted in that long-ago entry, trickle-down economics isn’t exactly showering Jack Monroe or Bernie Rosenthal with financial opportunities (the best job he can find is a bag boy position at a grocery store, and her glass-blowing shop is going out of business, thanks to ruthless rent hikes). Steve Rogers, on the other hand, possesses exactly the kinds of skills that will get you places in late-industrial capitalist society–he’s a commercial artist, and a good one!

Unfortunately for Cap, he’s got way too much on his plate (and his mind) to take advantage of this. One of the most significant moves that Gruenwald made early on is to re-extract his protagonist from the social matrix that Stern, Byrne and DeMatteis had embedded him in (i.e. the relationship with Bernie Rosenthal, making him a young urban professional). I LIKED those stories–and, in general, I PREFER a superhero character who is torn between his commitments to pure morality and intersubjective experience… however, Captain America is the most important exception to this personal rule. Why? Because, as I’ve mentioned in a variety of places, Cap isn’t a person. He’s the living symbol of an idea–and not the chauvinistic idea of a political state either–he is the embodiment of what Ralph Waldo Emerson would call “the infinitude of the private man.” What does that mean? Well, if I could put it simpler terms, you know I would! As it is, I’ll need about 150 blog posts to get the idea across…

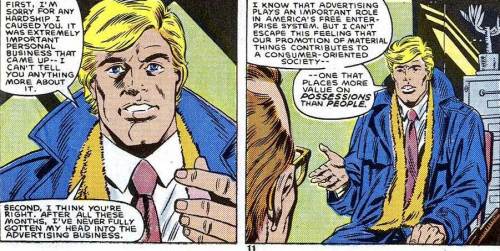

But one thing’s for sure–Cap shouldn’t work! That’s the biggest problem with Emerson’s vision of the ideal citizen–he (and Emerson is as weak on gender as you’d expect a 19th Century sage to be, despite his friendship with the extraordinary Margaret Fuller–author of Woman in the Nineteenth Century–which everyone should read… I’m just sayin’!) must be independently wealthy! So that’s something to keep in mind as we go along here… There’s a (financial) reason that Steve Rogers can engage in his half of this (American) dream conversation:

Gruenwald even lays some humour on us in the following panel, where Steve’s advertizing exec interlocutor exclaims: “Rogers! We’re talking about toothpaste here!”

The whole scene is ludicrous–and it’s not written in a way that’s going to appeal to the Alan Moore/Frank Miler comics-are-for-grownups crowd… or even the “I love you”/”And I you” comics-are-for-emo-misfits Claremont crowd–but it cuts directly to the core of the character’s psyche, in the tried and true expository cadences of Bronze Age superhero drama.

So! Gruenwald surgically removes the Peter Parker elements that his predecessors had grafted onto the character. Which doesn’t mean that Cap is that rarest of things, the Marvel character without problems. No. Cap’s destiny is to agonize over the greatest problem of all–the place of the well-intentioned citizen in establishing, maintaining and defending against the inevitable excesses of the political structures which give meaning and purpose to liberal-democratic existence. It’s the same problem that Gruenwald would soon treat in Squadron Supreme. And the one-two punch of that “maxi-series” and the 100-plus issue run on Captain America (to say nothing of his Foucauldian contributions to the New Universe in DP 7, The Pitt, The Draft and The War) make him the most interesting political philosopher in superhero writer’s clothing of the 1980s.

But let’s get back to the other eponymous characters who help to triangulate Gruenwald’s Cap in issue #309.

Nomad is Jack Monroe–a bizarre by-product of Marvel’s retroactive attempt to make sense of the Captain America character’s publication history… Steve Englehart brought him into the mix as Bucky-consort to the aberrant commie smashing Cap that rampaged through a few Timely titles during the mid-1950s, while the true Silver Age iteration of the character was on ice. After suffering through more than his share of troubles during the 1970s comics–including retroactively going insane thanks to improper Super Soldier treatments, watching his old partner take on the identity of the KKK-ish “Grand Director” and then being shot by the same deranged individual–Monroe takes advantage of Cap’s lingering weakness for wayward brown-haired youths (discussed at length by Jon M. Wilson and Michael Kaiser in their early Mighty Shield podcasts) and latches on as the true Cap’s partner.

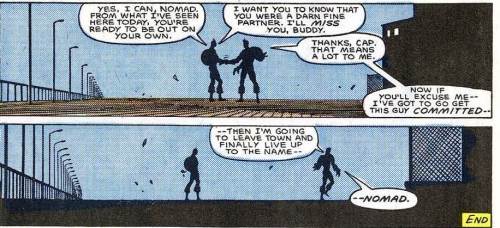

In #307, Gruenwald suggests that this isn’t necessarily the healthiest thing in the world for Jack (who begins seeing waking-nightmare half-Cap reflections of himself in store windows, and isn’t doing so well on the identity-formation front). In #309, we see Cap dealing with his side of this problematic codependency. As Steve himself will later sum up, the entire story drives toward our protagonist’s decision to stand by and do nothing, for a change:

The ever-perceptive Bernie Rosenthal, who will also soon be slipping out of Cap’s life, had previously paved the way for this scene by remarking upon Steve’s distressing need to control situations and his colleagues. This is the flip-side of Cap’s vaunted “natural leadership” qualities–which seem unambiguously good in the Avengers (at least since Cap and Hawkeye buried the hatchet after the initial turbulence of the “Cap’s Kooky Quartet” days).

Here again, the thematic imperative is to separate Cap from everything that distracts him from the central problematic of his living symbol existence. No sidekicks! No girlfriend (which is sad, ’cause I like Bernie–but she brings far too much balance into Cap’s life… Gruenwald’s version of the character will lone wolf it, until he hooks up with Diamondback–a former-criminal/fellow-adventurer who confronts Cap with more political/existential questions, rather than distracting him from them)! No middle-class job! Also–and this is REALLY important–no government work! (As Nick Fury spells out in this ominous panel–which looks ahead to the USA troubles that will bedevil Steve from issue #332 onward)

As the ultimate “blasted freelancer”, Gruenwald’s Cap is clearly on a collision course with Reaganite patriotism. He just doesn’t know it yet.

As the ultimate “blasted freelancer”, Gruenwald’s Cap is clearly on a collision course with Reaganite patriotism. He just doesn’t know it yet.

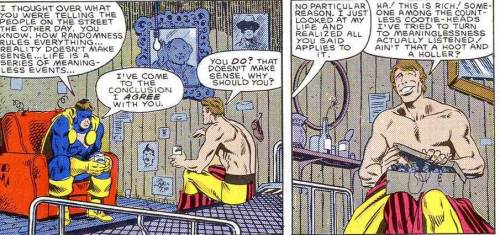

Cap and Nomad are on parallel reasoning paths throughout this issue. Jack Monroe stakes his entire future as an independent crimefighter on the quest to subdue Madcap. He succeeds by acting against all of the instincts which served him so badly in issue #307. Instead of charging fist first into confrontation, he elects to wheedle his way into Madcap’s confidence (if that’s the right word to use in reference to a person who has no confidence in anything). In a wonderfully strategic move, Jack takes advantage of the fact that even a prophet of absurdity can easily be won over by the pretense of conversion. The words “you’re right” are the most powerful tools in a canny fighter’s arsenal.

And what about the object of this quest?

We first meet Madcap (this issue) cavorting blithely through a pretty clear “gay bashing” scenario (Gruenwald’s horror of American redneckery is a constant, but it’s especially prominent here and in the sequences of Squadron Supreme which focus on the need to reclaim America from red statism, by superheroic force, if necessary):

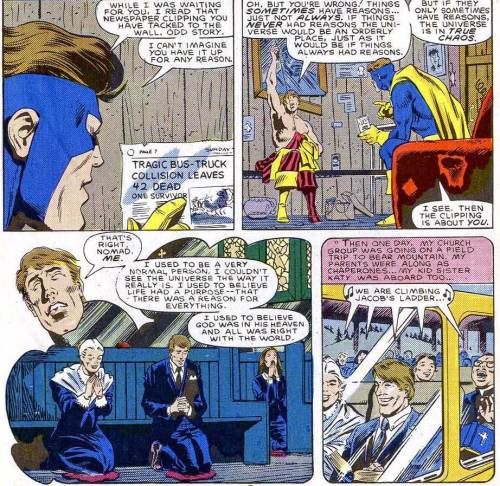

But Madcap is just as much a product of the American heartland as pro-lifery, Tea Baggism and apple pie–he was raised as an evangelical Christian! But I’ll let him explain it:

He’s a pretty sophisticated philosopher–a Gruenwald trait–for a guy who traipses around in yellow, toting a “fun gun”.

He’s a pretty sophisticated philosopher–a Gruenwald trait–for a guy who traipses around in yellow, toting a “fun gun”.

But then again, this is the kind of incident that’ll make just about anyone into the Messenger of Meaninglessness–and Madcap plunges into that new role with all of the fervour that he had once channeled into his faith in Christ:

Again–and I pointed this out in the entry on #307–Nomad offers no counterargument to Madcap’s claims re: the absurdity of the universe. What possible response could there be? Cosmic meaninglessness is a given in a Gruenwald book. But then again, so is existentialist commitment. That’s what everyone prior to Gruenwald had gotten so wrong about Cap. He’s NOT a blind optimist. NOT a “patriot”. NOT in favour of “life, liberty and the American Way.” What he is, is a person who believes more fervently than anyone else in the individual’s duty to (in Charles Dickens’ immortal phrasing–from A Christmas Carol) “interfere for good in human matters, before [he or she] loses the power forever.” He’s the Ultimate New Dealer, minus the cynical political calculation of Rooseveltian Democrats.

Gruenwald’s epic tenure on the book will derive all of its extraordinary dynamism from the confrontation between this unique iteration of Cap and 1980s America–a most uncongenial place for a New Dealer to deal with. And as the concluding panels of #309 (which remove Nomad and Madcap) make clear, he’ll have to do it on his own, as he always should have been.

More soon!

Thanks for reading!

Dave